At Russia museum, Elgin Marbles statue is cast in a political light

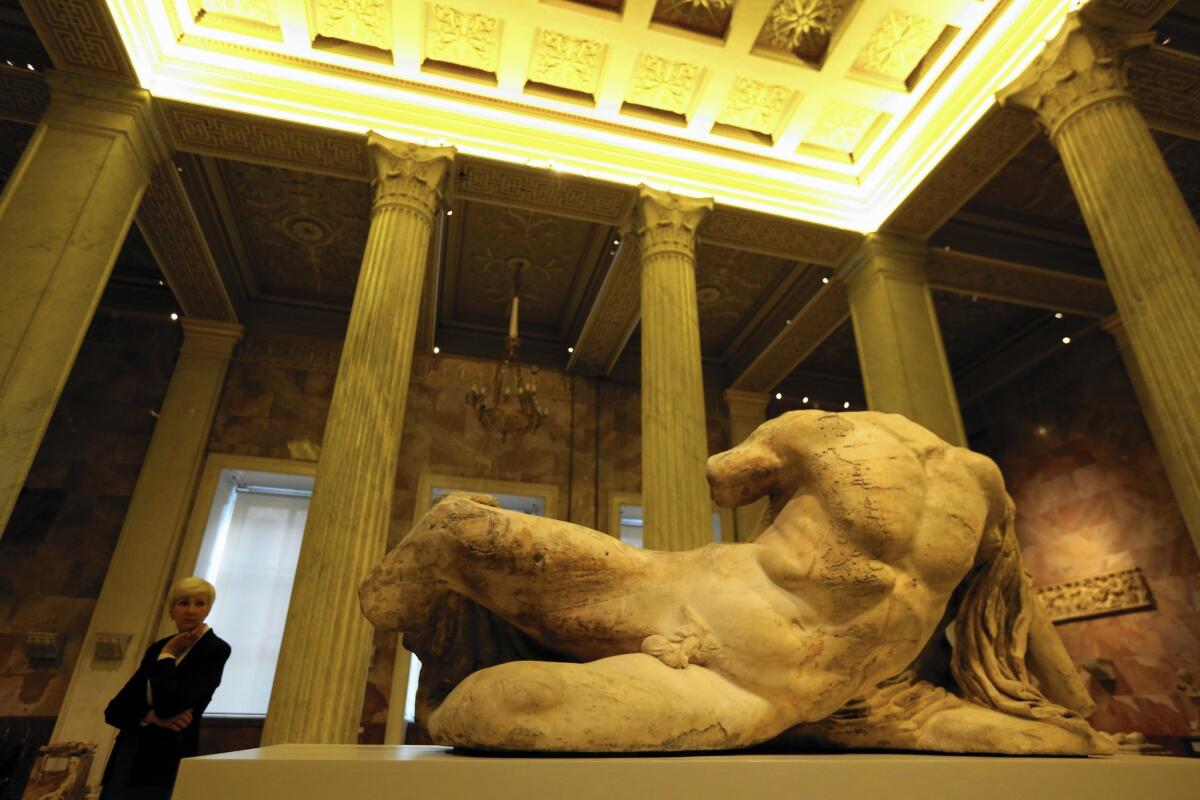

Some stared in awe at the impeccable 25-century-old statue. Some walked past without even stopping. “It is not in their program,” explained a mentor for the latter group of giggling schoolchildren.

One visitor suggested that Russia hold on to the iconic artwork rather than return it to Britain in mid-January at the conclusion of its short-term loan.

And then there was the orderly group of somber-faced police cadets, who were intently observing the headless, handless and footless statue of the Greek river god Ilissos.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Elgin Marbles: An article in the Dec. 19 Section A about a debate over the British Museum’s loan of the Ilissos statue to the State Hermitage Museum in Russia described the 2,500-year-old statue as being 100 times older than the Hermitage museum. The statue is 10 times older than the museum, which is marking its 250th year. —

------------

“That one will be hard to identify and solve,” said one of the junior detectives, evoking suppressed chuckles from his classmates.

The statue gazers — and non-gazers — had come on a gray, windy December afternoon to the darkened but warm halls of the State Hermitage Museum, which is celebrating its 250th anniversary, to view the hundred-times older Elgin Marbles piece, on loan for the occasion from the British Museum.

The reclining male figure from the west pediment of the Parthenon in Athens was first dismantled more than 200 years ago and taken to London by a British diplomat. The Greek government has long insisted that the Marbles were looted and seeks their return.

The decision to lend it to Russia is almost as controversial, with critics calling Britain’s gesture of cultural goodwill an act of ill-advised appeasement toward Russia’s recalcitrant president, Vladimir Putin.

At the Hermitage, few visitors seemed aware of the controversy surrounding the marble sculpture, whose presence here has been described by British Museum trustees as “a cause for celebration” for an anniversary that provides “the context to this significant loan.”

The other obvious context these days is the soaring tension between Russia and leading Western powers including Britain over Moscow’s March annexation of Crimea and its continuing support for pro-Russia rebels in eastern Ukraine. The moves have triggered international sanctions and perhaps the most significant East-West crisis since the Cold War.

“Most visitors I’ve spoken to these days talked about the sanctions and were amazed how [Mikhail] Piotrovsky [the longtime Hermitage general director] pulled it off at such a difficult time for Russia,” exhibit hall guardian Valentina Pavlova said. “One man said we should keep the exhibit just in case. You never know where things may go now that the whole world seems to be against us.”

Pavlova watched with some dismay as the group of schoolchildren was ushered into an adjacent hall.The noisy youngsters were followed by the clueless police cadets.

Also on hand was artist Tatiana Frolova, a Putin supporter who specializes in tombstone portraits. Frolova, in her mid-50s, saw poignant symbolism in the controversy over the marbles’ ownership.

“The Brits are holding on to this collection and they are doing the best they can to show it in a proper light to millions of people,” she said. “So Putin is right in a similar way when he says that we will keep Crimea as part of Russia and make it open and suitable to be enjoyed by the entire world too. Whether it was a mistake or not, I trust Putin and I am confident he is acting in the best interests of Russia.”

The Marbles exhibit, which was prepared in secrecy and opened on Dec. 5 with little pomp, has been visited by Putin, adding political weight to an otherwise cultural and historic moment.

“Vladimir Vladimirovich stopped for some time in front of the statue and spoke amicably with Piotrovsky, but his face looked tired,” Pavlova recalled. “We were waiting for this visit and some spent a night inside the museum.”

Curator Anna Trofimova agrees that the exhibition, coming when it has, carries political overtones. But she contends that holding it now “may build a new bridge of understanding between Russia and the West at a time when many other such bridges are being dismantled.”

“Our museums sent a joint message to the rest of the world: Let’s trust each other and let’s work together for humanitarian ideals and democracy promoted for centuries by this marvelous collection,” said Trofimova, who considers the exhibition the high point of her career. “This is exactly the case when beauty may save the world.

“For us scientists, nothing changed with the change in Crimea’s status,” said Trofimova, the Hermitage’s ancient world department chief. “Our archaeological teams worked there under the Soviet Union, under independent Ukraine and now we have six teams in the field who leave all the artifacts they find in the custody of local museums as usual.”

As she spoke, a group of 9-year-olds came into the exhibition hall. They stood staring as their guide told them: “Look at the back of the statue. It is done as artfully and meticulously as the front, but no one could see it in the temple as it was always against the wall.

“Would you do your homework as thoroughly if you knew that neither your mom or class teacher see and check it?”

“No!” the kids replied in chorus.

“See my point?” the guide concluded.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.